Nani has a gift for entering others’ cultures in a respectful and sensitive way. That gift, combined with her strong curiosity and sense of adventure, has led to a unique trajectory from her childhood in Indonesia to her current job as a project manager at LinkedIn. This is the first in an eight-part interview I conducted with Nani.

Sarah: What’s your current position?

Nani: Currently I manage localization marketing projects for LinkedIn— primarily for the European and Latin American markets.

Sarah: Can you explain what that entails?

Nani: My team, the localization team, partners with marketers in various business units to localize their marketing content and campaigns. That means we translate and localize marketing communications into local languages. Localization requires sensitivity not just to language but also to cultural factors.

Sarah: Help me understand the nuts and bolts of what you do.

Nani: My job comprises two major elements: active project management and relationship building. On the project management front, I make sure all the localized content is delivered on time—I build timelines, coordinate with marketing partners and vendors and manage tickets for all the projects in progress as well as our backlog.

The other part of my work is to drive strategy and plan with our partners. Localization is often thought of at the end of a marketing project, but really it should be planned for up front. Most of the content creators are based in the US and are still accustomed to thinking in terms of a US audience. But once a marketing piece—let’s say, an e-book with a really nice, polished design—has been produced in English, it’s challenging to go back in at that point and figure out how to create a parallel version in German. If the content creators are planning for localization from the beginning, it’s a lot easier.

So I engage with them early in the process and say, OK, it’s going to be hard to localize this image of San Francisco during the World Series for other markets, because it’s so specific to the San Francisco Bay Area. Or, this quote by Tori Amos might not be relevant to people in Germany or Spain. I’ll suggest they find a more globally relevant example. I’m not the final decision maker, and some teams are more receptive to feedback and changes than others. But I work hard to build relationships and stay engaged with our partners, especially the content creators.

Sarah: I’ve known you for most of your adult life, and you’ve explored a number of interests over the years. It hasn’t been a linear path. Yet looking back, it all seems to support what you’re doing currently. I see this conversation as a chance to trace your path with you. Let’s back way up. You grew up in Indonesia—where exactly?

In West Java, in Bandung, the third largest city in Indonesia.

Sixth birthday.

Sarah: Were you thinking one day you’d move to the States?

Nani: As a child, I resisted a lot of the norms, customs, and rules around me. I couldn’t find anything to feel passionate about. I grew up in a community of Chinese Indonesians where people knew each other’s business and talk amongst themselves about the latest thing that so-and-so’s son or daughter has done.

Sarah: Were you insulated from non-Chinese Indonesians?

Nani: I went to the same school from kindergarten through high school—14 years—and about 90 percent of the students were Chinese Indonesians. I did have a couple native Indonesian friends. But as kids, we never explicitly addressed racial issues.

Seventh birthday.

Sarah: Was there a sense in the Chinese Indonesian community of needing to stick to their own due to discrimination by the wider culture?

Nani: That’s a narrative that is real for many Chinese Indonesians. But I also think Chinese Indonesians tend to use that narrative in order to hold ourselves apart. The discrimination is real, it’s there—but sometimes, like many racial issues, the perception of discrimination is tied up with lack of openness to one another.

Maybe I was naïve, but it was very rare that I was directly discriminated against for being Chinese. That might be due in part to the fact that my skin color is darker than that of many Chinese Indonesians. Once a cousin of mine, who like me has darker skin, was out with her friends, who were all Chinese Indonesian. They were mugged by a native Indonesian. When he got to my cousin he stopped and said, I’m not going to do this to one of my own people.

Sarah: So it sounds like you didn’t feel like an outsider so much in terms of the larger culture, but you did feel that somehow you weren’t connecting. Can you tell me more about that?

Nani: I felt like I had to conform to what was expected of me, but I didn’t want to. I did very poorly in my first decade of school; I just wasn’t interested. The subjects emphasized in the Indonesian educational system are life sciences and math. I felt pressure from my parents to be like some of my cousins, who excelled in those subjects.

Eighth birthday.

I also felt pressure from my peers and family to be a certain type of girl, very feminine and materialistic. People were wearing a lot of American brands—Guess, Esprit—they were eager to catch up with all these Western materialistic obsessions.

On the other hand, I loved watching and imitating English-language TV shows like Beverly Hills 90210 and a Canadian series called MacGyver, about a resourceful guy who gets himself out of crazy situations. The emotional language is so different—Indonesians don’t speak about their emotions the way people do in North America. I’d hang out by myself in my bedroom and practice talking like these characters, saying things like, “How do you feel?”

Next: Such a Bad Kid

-

August 2021

- Aug 31, 2021 The Heart Is the Major Target—Part 9: The Teacher Role Isn't My Essence Aug 31, 2021

-

June 2021

- Jun 13, 2021 The Heart Is the Major Target—Part 8: Machines Spilling Out Teachers Jun 13, 2021

-

April 2021

- Apr 14, 2021 The Heart Is the Major Target—Part 7: A Waterfall of Inspiration Apr 14, 2021

-

February 2021

- Feb 14, 2021 The Heart Is the Major Target—Part 6: Grab the Right Computer File Feb 14, 2021

-

December 2020

- Dec 26, 2020 The Heart Is the Major Target—Part 5: Yoga Is My Second Child Dec 26, 2020

-

November 2020

- Nov 5, 2020 The Heart Is the Major Target—Part 4: Wow, This Is Me Nov 5, 2020

-

October 2020

- Oct 4, 2020 The Heart Is the Major Target—Part 3: In Exile in My Own Country Oct 4, 2020

-

August 2020

- Aug 23, 2020 The Heart Is the Major Target—Part 2: Openness to the Unseen Aug 23, 2020

- Aug 2, 2020 The Heart Is the Major Target—Part 1: Let's Move Around; We'll Feel Better Aug 2, 2020

-

July 2020

- Jul 25, 2020 Educator Wellness Series Conclusion: Moving Forward with Wellness Jul 25, 2020

- Jul 6, 2020 Educator Wellness Practice #10: Inhabiting the Dignified Stance of "Adequate" Jul 6, 2020

-

June 2020

- Jun 17, 2020 Educator Wellness Practice #9: Jun 17, 2020

- Jun 3, 2020 Educator Wellness Practice #8: Reducing Stress Through Body Scanning Jun 3, 2020

-

May 2020

- May 21, 2020 Facebook Live Event: A Conversation About the Impact of Saying Goodbye to Students May 21, 2020

- May 13, 2020 Educator Wellness Practice #7: Setting Intention and Letting Go of Results May 13, 2020

- May 6, 2020 Educator Wellness Practice #6: Practicing Goodwill as Self-Care May 6, 2020

-

April 2020

- Apr 29, 2020 Educator Wellness Practice #5: Dealing with Constant Change Apr 29, 2020

- Apr 22, 2020 Educator Wellness Practice #4: Listening to Silence Apr 22, 2020

- Apr 21, 2020 Facebook Live Event: A Conversation About the Importance of Self-Care Apr 21, 2020

- Apr 15, 2020 Educator Wellness Practice #3: Apr 15, 2020

- Apr 8, 2020 Educator Wellness Practice #2: Engaging Wisely with News and Media Apr 8, 2020

- Apr 1, 2020 Educator Wellness Practice #1: Breathe ... Keep Breathing Apr 1, 2020

-

March 2020

- Mar 25, 2020 Educator Wellness Series for Collaborative Classroom Mar 25, 2020

-

May 2019

- May 19, 2019 Managing to Build Bridges - Part 8: Do We Want to Be Right in a Dictionary Sense? May 19, 2019

-

April 2019

- Apr 27, 2019 Managing to Build Bridges - Part 7: You Just Need to Find a Good Husband Apr 27, 2019

- Apr 6, 2019 Managing to Build Bridges - Part 6: Human Remains and Cultural Artifacts Apr 6, 2019

-

March 2019

- Mar 17, 2019 Managing to Build Bridges - Part 5: Poetry Has No Rules Mar 17, 2019

- Mar 3, 2019 Managing to Build Bridges - Part 4: Dessert Goes to a Different Stomach Mar 3, 2019

-

January 2019

- Jan 13, 2019 Managing to Build Bridges - Part 3: I Felt Pretty Stupid Jan 13, 2019

-

December 2018

- Dec 9, 2018 Managing to Build Bridges - Part 2: Such a Bad Kid Dec 9, 2018

-

November 2018

- Nov 23, 2018 Managing to Build Bridges - Part 1: The Pressure to Be a Certain Type of Girl Nov 23, 2018

-

October 2018

- Oct 23, 2018 Leadership Without Ego - Part 6: Mayberry with an Edge Oct 23, 2018

- Oct 1, 2018 Leadership Without Ego - Part 5: Everyone Everywhere Deserves to Make Art Oct 1, 2018

-

September 2018

- Sep 10, 2018 Leadership Without Ego - Part 4: I'm About Ready to Swear Sep 10, 2018

-

August 2018

- Aug 19, 2018 Leadership Without Ego - Part 3: The Dalai Lama Breaks All the Rules Aug 19, 2018

-

July 2018

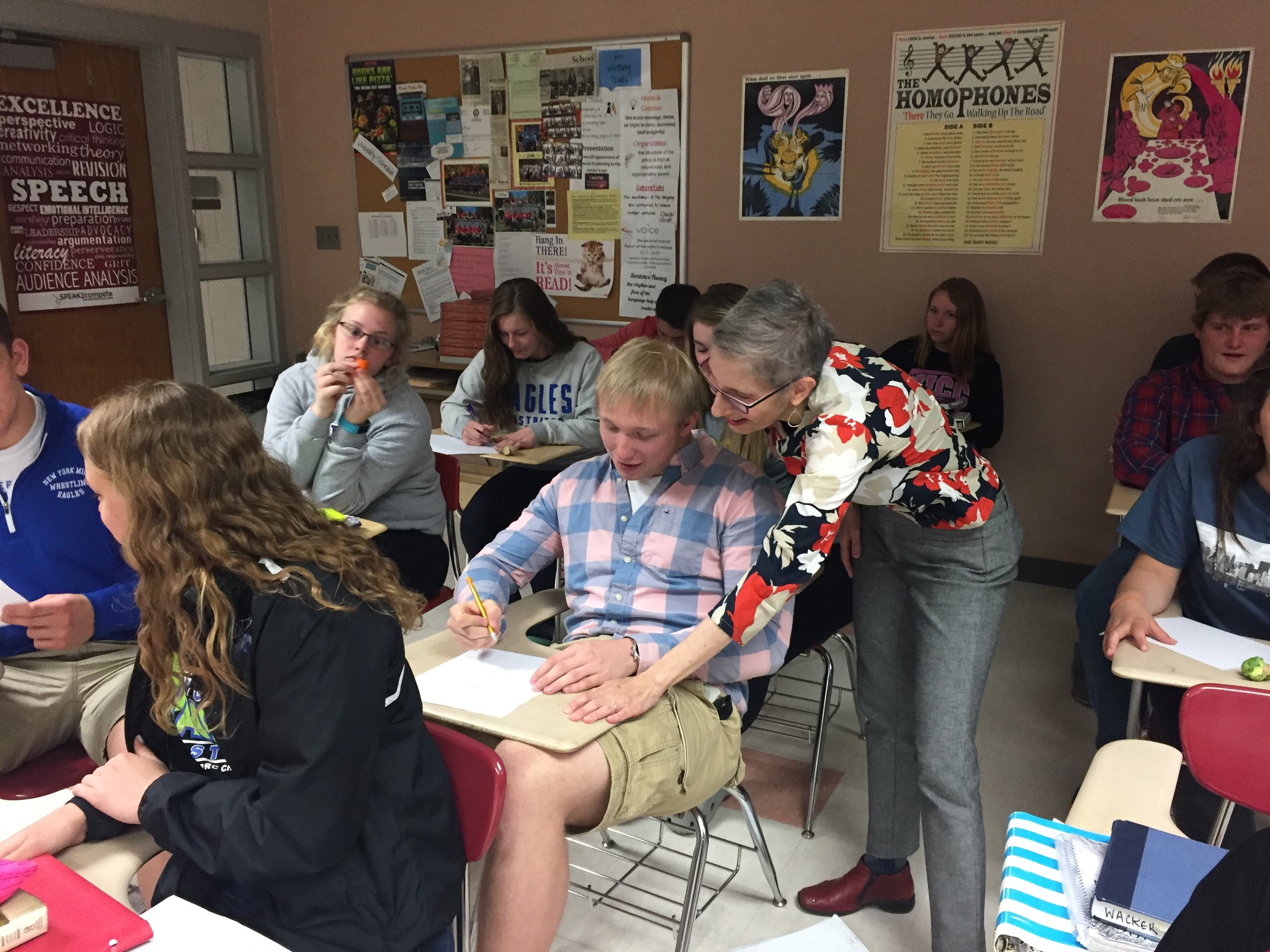

- Jul 29, 2018 Leadership Without Ego - Part 2: The Kids Melted Under That Praise Jul 29, 2018

- Jul 10, 2018 Leadership Without Ego - Part 1: The Workshop Was Neutral Territory Jul 10, 2018

-

May 2018

- May 26, 2018 The Alchemy of Service - Part 5: Watch Out, Someone's Behind You May 26, 2018

- May 6, 2018 The Alchemy of Service - Part 4: Fireworks and Tears May 6, 2018

- May 5, 2018 The Alchemy of Service - Part 3: Joann Wong! You Are Chinese! May 5, 2018

-

April 2018

- Apr 6, 2018 The Alchemy of Service - Part 2: Mom, It's Only a Nickel Apr 6, 2018

-

March 2018

- Mar 19, 2018 The Alchemy of Service - Part 1: Mouse Soup Mar 19, 2018

-

February 2018

- Feb 18, 2018 Back to the Garden - Part 4: Mountain Lion Footprints on the Deck Feb 18, 2018

- Feb 3, 2018 Back to the Garden - Part 3: "You're a Good Egg—Happy Easter" Feb 3, 2018

-

January 2018

- Jan 15, 2018 Back to the Garden - Part 2: "A Pretty Big Failure" Jan 15, 2018

- Jan 1, 2018 Back to the Garden - Part 1: "Aesthetic Shock" Jan 1, 2018

-

August 2017

- Aug 15, 2017 Goodbye Self-esteem, Hello Self-compassion – Part 3: Real Love Aug 15, 2017

-

July 2017

- Jul 31, 2017 Goodbye Self-esteem, Hello Self-compassion – Part 2: Mirror, Mirror Jul 31, 2017

- Jul 17, 2017 Goodbye Self-esteem, Hello Self-compassion – Part 1: Bashing Vasco Jul 17, 2017

-

May 2017

- May 28, 2017 This Thing I Found: Teens Teach Us How to See Freshly May 28, 2017

-

March 2017

- Mar 20, 2017 Dream On - Part 6: Dream Analysis Example Mar 20, 2017

- Mar 7, 2017 Dream On - Part 5: A Dream Analysis Technique (cont.) Mar 7, 2017

-

February 2017

- Feb 20, 2017 Dream On - Part 4: A Dream Analysis Technique Feb 20, 2017

-

January 2017

- Jan 22, 2017 Dream On - Part 3: Recording Dreams Jan 22, 2017

- Jan 15, 2017 Dream On - Part 2: Dream Recall Jan 15, 2017

-

December 2016

- Dec 30, 2016 Dream On – Part 1 Dec 30, 2016

- Dec 12, 2016 Enjoying the Ride of Serendipity Dec 12, 2016

- Dec 6, 2016 Agnes Martin: A Singular Career Dec 6, 2016