Steve Emrick never sought to be a leader—but leadership found him. This is the second in a six-part series of posts based on an interview I conducted with Steve about his three decades running arts programs in California’s prison system. In Section 1, we left off with Steve explaining that after running the Tehachapi Prison arts program, he transitioned to a position at Deuel Vocational Institute in Tracy, CA.

Steve: When I went to DVI I got involved with the William James Association.

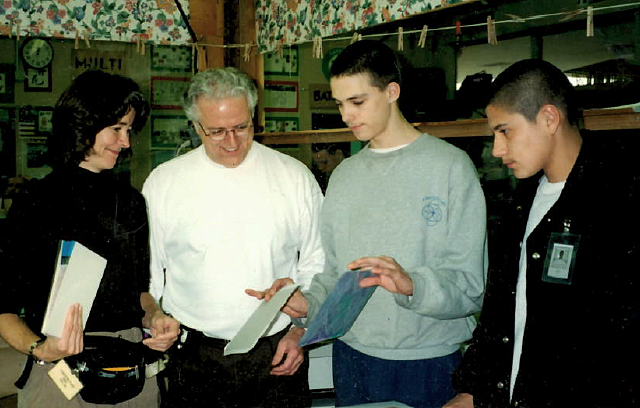

Steve with DVI arts program alumni Dennis Cookes and Robert Vincent at a conference on arts in the prisons.

Sarah: Tell me about William James.

Steve: It’s a nonprofit that contracts with the Department of Corrections to place artist teachers in prisons in Northern California. William James screens and places the artists and ensures that they get paid in timely way. I’d let the William James staff know what kinds of artists I needed, and they’d do the matchmaking. I developed a close working relationship with the executive director, Laurie Brooks—which proved important strategically later on. But I’m getting ahead of myself.

I ran DVI’s art program through most of 90s. The program was already in place when I got there, in a very nice studio space set up by artist Bobby Altman. We offered woodworking (I taught that class), guitar making, ceramics, painting and drawing, and music. The program was hugely successful. We had a core group of inmates who were dedicated artists, and because of that we were able to raise ten grand a year through art sales, and give visibility to the artwork. We contributed all the proceeds to the Child Abuse Prevention Council of San Juaquin Valley.

I still have a close connection with a lot of those guys, many of whom are out now. They’re off parole, citizens with good jobs who are still making art. One big success story is Vincent, who learned to make guitars at DVI. He’s been out 15 or 20 years now, and he makes high-end classical guitars for a living. His son is also an artist and has become a prison arts teacher.

DVI arts program alumnus Robert Vincent with a guitar he made.

Around 1998, I was feeling burnt out at DVI and wanted to try something different. I took a position at the Youth Authority in Stockton. I coordinated programs in six juvenile facilities for young people aged 14–26. I found that work a lot more heart wrenching than working with adults. At that young age, you really can’t argue that these kids are locked up through any fault of their own. The staff were more encouraging than at the adult prisons but the environment was still draconian. Officers, barbed wire fences. And kids are harder to deal with in those environments. Fistfights would erupt.

Wards and painting instructor working on a mural at Youth Authority.

The worst moment for me was one time in a paper marbling workshop. One kid was trying to become a big shot in one of the gangs. I saw him order two other kids to clean up his area. I said, No, everyone cleans up his own area. He started to walk away from me. I grabbed his shoulder. He whipped around and said, Don’t ever touch me again—you don’t know what might happen. He was the kind of kid who could have played that up, because there’s a rule against touching the kids. The art teacher called in officers and they dealt with him. At that moment I realized, OK, I don’t have the patience that’s required to work in this environment.

Working with juveniles wasn’t the only aspect of that job I didn’t click with. I’d gone from managing my own program to managing programs in six different places. There are always problems that crop up when you’re bringing people inside—for example, the artist doesn’t have the proper paperwork or messes up a protocol. Previously, when I was running my own program, I had credibility among the staff, so I knew who to call to resolve an issue. But in this situation a lot of my work was by phone. So I couldn’t be as effective.

Wards making books.

Sarah: Were there any heartening moments there?

Steve, book artist Beth Thielen, and wards in bookbinding workshop.

Definitely. I remember a bookbinding workshop where the instructor had the kids making these very complicated books. They were really into it. We had photos posted of them holding their completed books—they were so proud. Others would see the pictures and say, Hey, that looks really cool! The kids melted under that praise. They were so starved for positive attention and feedback.

We had a unit for kids with mental dysfunction. I wanted to place this older woman artist in there as a grandmother figure. At first the administration resisted because they thought the kids would act out. But eventually we were able to get her in there. This one kid was especially dysfunctional—he’d refuse to bathe, spread feces all over his cell. We got him into this class. The staff would tell him, You really need to watch it this week because she’s coming on Saturday and you want to get out to go to your class! He totally improved his behavior.

Steve and Beth admiring a ward's work on a book project as another ward looks on.

Wards proudly displaying elaborate handmade journals.

The Youth Authority staff started realizing that instead of this program being an impediment, it could really help them. They started picking out the kids with the worst problems to send to art class. And other juvenile facilities started requesting art programs.

Youth Authority artist teachers with Laurie Brooks (third from left).

But even though I saw lots of positive things happen there, I still wanted to go back to working with adults. And my family wanted to move closer to the hub of the Bay Area. So in 2003, I took a job running the arts program at San Quentin. The person who’d been running that program had moved into an education position at the prison.

That program was very successful as well. But right when I got there, the Department of Corrections eliminated their contracts with William James and another nonprofit that provided the same service for Southern California prisons. Soon after that, my own position was moved under the prison education department. I lost a lot of independence. I was assigned to a program called Bridging, which serves inmates in the reception center. The reception center holds guys in the process of transitioning from county jail to prisons all over the state. Until this point the Department of Corrections had not provided programs for that population. So the Bridging program was an attempt to remedy that. I set up drawing, poetry, origami, and collage classes. These were short-term classes because the guys were shipped off to other prisons after six weeks or so. One of the challenges of that job was that the inmates were assigned to these classes, whereas in the past, I’d only worked with guys who volunteered to take art classes. So it meant I was working with students who didn’t necessarily want to be in class.

William James executive director Laurie Brooks and I started strategizing about how to keep prison arts programming alive. Laurie and Jack Bowers, a retired artist facilitator, testified before the state legislature. But that work didn’t bear fruit right away. We survived in those years on small grants from nonprofits.

Laurie Brooks, Alma Robinson, and Jack Bowers presenting at a conference on arts in the prisons.

Next installment: The Dalai Lama Breaks All the Rules